Layout.superpose [text_room; image_room], then the text would have been hidden by the colored box (if the color was opaque). Houses and rooms

Bogue makes use of the housing metaphor: the group is called a house, and it contains two rooms: one for the image, one for the text.

There are three basic ways of constructing a house:

- A flat: rooms are positionned next to each other, using

Layout.flat. - A tower: rooms are positionned on top of each other, using

Layout.tower. - A free arrangement, using

Layout.superpose. In this case, overlapping rooms is permitted.

Let's show how it works in practice. For this tutorial, we need to have several "test layouts", so let's write a generic function to construct them. Instead of an image, a plain colored box will do.

open Bogue

let make_layout ?(w=120) ?(h=90) color text =

let text_room = Layout.resident (Widget.label text) in

let style = Style.(of_bg (color_bg color)) in

let image_room = Layout.resident (Widget.box ~w ~h ~style ()) in

Layout.superpose [image_room; text_room]Notice that the house is created by using superpose; by default, image_room and text_room have coordinates (x,y)=(0,0), so by superposing them, the text will appear in the top left corner.

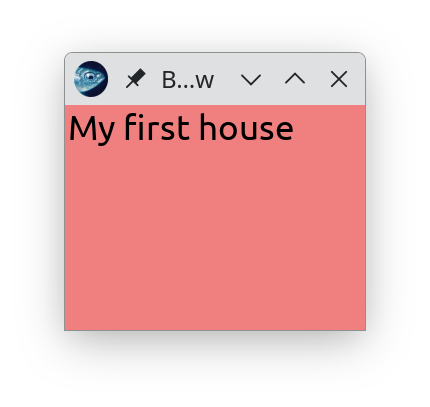

Let's see what this gives. We may create a Bogue app with this sole "house", as follows.

let () =

make_layout Draw.(opaque (find_color "lightcoral")) "My first house"

|> Bogue.of_layout

|> Bogue.run

Notice that the rooms and the house in fact have the same type: they are all Layouts. Why is that? It's because we want to have the possibility to make "groups of groups", or even "groups of groups of groups", and so on. For instance, let's put three of the above layouts next to each other...

let r1 = make_layout Draw.(opaque (find_color "lightcoral")) "Layout 1"

let r2 = make_layout Draw.(opaque (find_color "gold")) "Layout 2"

let r3 = make_layout Draw.(opaque (find_color "lightgreen")) "Layout 3"

let () =

let house = Layout.flat ~name:"A flat" [r1; r2; r3] in

Bogue.(run (of_layout house))

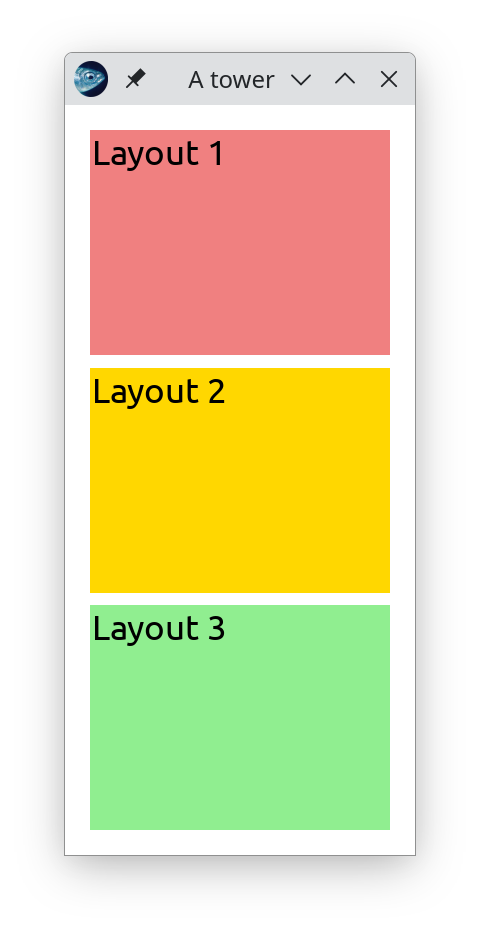

... or on top of each other:

let () =

let house = Layout.tower ~name:"A tower" [r1; r2; r3] in

Bogue.(run (of_layout house))

Now let's make a new house out of two houses: we position a flat and a tower next to each other.

let r4 = make_layout Draw.(opaque (find_color "paleturquoise")) "Layout 4"

let r5 = make_layout Draw.(opaque (find_color "plum")) "Layout 5"

let () =

let flat = Layout.flat [r1; r2; r3] in

let tower = Layout.tower [r4; r5] in

let house = Layout.flat [flat; tower] in

Bogue.(run (of_layout house))

A Tree structure

From what we have done, it's clear that the set of all layouts form what is called in computer science or mathematics a tree. The trunk is the largest layout, making up the whole window; in the example above, this is house. Then we have two branches, corresponding to the groups contained in this window: flat and tower. The flat branch splits into three new branches r1, r2, and r3, while the tower branch splits into two new branches r4 and r5. Each of these branches is again split into two new branches: the text and the image. These final layouts (text and image) do not contain any other group: in Bogue's terminology, they are called resident; in the tree language, they are leaves. Leaves always contain widgets. (Here, the "text" layout contains a label widget, and the "image" layout contains a box widget.)

Following the tradition (for instance, think of family trees) we present the tree upside-down: the trunk is the "top layout".

Summary

In Bogue, layouts are used to position the widgets in the window. The set of all layouts form a tree. A layout can either contain a widget, in which case it is a leaf, or a list of layouts, in which case it is a node. We often call such a node a house, and the layouts in the list are the rooms.

A practical consequence is that the layout structure must be constructed in a "bottom-up" fashion: always start from the leaves, and the trunk is the last layout we construct. The final Bogue app is constructed from this trunk, using Bogue.of_layout.

Bogue.of_layouts. Dynamical layouts

The tree structure we've just described is perfect for static layouts. When designing our app, we can sketch the GUI on a piece of paper, find out the corresponding tree, and then implement it in Bogue, starting from the leaves, and grouping them step by step, up to the trunk.

However, very often, GUI are nicer when they have dynamic (or "responsive") components. For instance, what happens if Layout r3, in response to some user interaction, wants to modify Layout flat, to which it belongs? This is the subject of the Self-modifying layouts tutorial.