Functional Programming

What is functional programming?

We've got quite far into the tutorial, yet we haven't really considered

functional programming. All of the features given so far - rich data

types, pattern matching, type inference, nested functions - you could

imagine could exist in a kind of "super C" language. These are Cool

Features certainly, and make your code concise, easy to read, and have

fewer bugs, but they actually have very little to do with functional

programming. In fact my argument is going to be that the reason that

functional languages are so great is not because of functional

programming, but because we've been stuck with C-like languages for

years and in the meantime the cutting edge of programming has moved on

considerably. So while we were writing

struct { int type; union { ... } } for the umpteenth time, ML and

Haskell programmers had safe variants and pattern matching on datatypes.

While we were being careful to free all our mallocs, there have been

languages with garbage collectors able to outperform hand-coding since

the 80s.

Well, after that I'd better tell you what functional programming is anyhow.

The basic, and not very enlightening definition is this: in a functional language, functions are first-class citizens.

Lot of words there that don't really make much sense. So let's have an example:

# let double x = x * 2 in

List.map double [ 1; 2; 3 ];;

- : int list = [2; 4; 6]

In this example, I've first defined a nested function called double

which takes an argument x and returns x * 2. Then map calls

double on each element of the given list ([1; 2; 3]) to produce the

result: a list with each number doubled.

map is known as a higher-order function (HOF). Higher-order

functions are just a fancy way of saying that the function takes a

function as one of its arguments.

So far so simple. If you're familiar with C/C++ then this looks like

passing a function pointer around. Java has some sort of abomination

called an anonymous class which is like a dumbed-down, slow and

long-winded closure. If you know Perl then you probably already know and

use Perl's closures and Perl's map function, which is exactly what

we're talking about. The fact is that Perl is actually quite a good

functional language.

Closures are functions which carry around some of the "environment"

in which they were defined. In particular, a closure can reference

variables which were available at the point of its definition. Let's

generalise the function above so that now we can take any list of

integers and multiply each element by an arbitrary value n:

# let multiply n list =

let f x =

n * x in

List.map f list;;

val multiply : int -> int list -> int list = <fun>

Hence:

# multiply 2 [1; 2; 3];;

- : int list = [2; 4; 6]

# multiply 5 [1; 2; 3];;

- : int list = [5; 10; 15]

The important point to note about the multiply function is the nested

function f. This is a closure. Look at how f uses the value of n

which isn't actually passed as an explicit argument to f. Instead f

picks it up from its environment - it's an argument to the multiply

function and hence available within this function.

This might sound straightforward, but let's look a bit closer at that

call to map: List.map f list.

map is defined in the List module, far away from the current code.

In other words, we're passing f into a module defined "a long time

ago, in a galaxy far far away". For all we know that code might pass f

to other modules, or save a reference to f somewhere and call it

later. Whether it does this or not, the closure will ensure that f

always has access back to its parental environment, and to n.

Here's a real example from lablgtk. This is actually a method on a class (we haven't talked about classes and objects yet, but just think of it as a function definition for now).

class html_skel obj = object (self)

...

...

method save_to_channel chan =

let receiver_fn content =

output_string chan content;

true in

save obj receiver_fn

...

endFirst of all you need to know that the save function called at the end

of the method takes as its second argument a function (receiver_fn).

It repeatedly calls receiver_fn with snippets of text from the widget

that it's trying to save.

Now look at the definition of receiver_fn. This function is a closure

alright because it keeps a reference to chan from its environment.

Partial function applications and currying

Let's define a plus function which just adds two integers:

# let plus a b =

a + b;;

val plus : int -> int -> int = <fun>

Some questions for people asleep at the back of the class.

- What is

plus? - What is

plus 2 3? - What is

plus 2?

Question 1 is easy. plus is a function, it takes two arguments which

are integers and it returns an integer. We write its type like this:

plus : int -> int -> intQuestion 2 is even easier. plus 2 3 is a number, the integer 5. We

write its value and type like this:

5 : intBut what about question 3? It looks like plus 2 is a mistake, a bug.

In fact, however, it isn't. If we type this into the OCaml

interactive toplevel, it

tells us:

# plus 2;;

- : int -> int = <fun>

This isn't an error. It's telling us that plus 2 is in fact a

function, which takes an int and returns an int. What sort of

function is this? We experiment by first of all giving this mysterious

function a name (f), and then trying it out on a few integers to see

what it does:

# let f = plus 2;;

val f : int -> int = <fun>

# f 10;;

- : int = 12

# f 15;;

- : int = 17

# f 99;;

- : int = 101

In engineering this is sufficient proof by example

for us to state that plus 2 is the function which adds 2 to things.

Going back to the original definition, let's "fill in" the first

argument (a) setting it to 2 to get:

let plus 2 b = (* This is not real OCaml code! *)

2 + bYou can kind of see, I hope, why plus 2 is the function which adds 2

to things.

Looking at the types of these expressions we may be able to see some

rationale for the strange -> arrow notation used for function types:

plus : int -> int -> int

plus 2 : int -> int

plus 2 3 : intThis process is called currying (or perhaps it's called uncurrying, I never was really sure which was which). It is called this after Haskell Curry who did some important stuff related to the lambda calculus. Since I'm trying to avoid entering into the mathematics behind OCaml because that makes for a very boring and irrelevant tutorial, I won't go any further on the subject. You can find much more information about currying if it interests you by doing a search on Google.

Remember our double and multiply functions from earlier on?

multiply was defined as this:

# let multiply n list =

let f x =

n * x in

List.map f list;;

val multiply : int -> int list -> int list = <fun>

We can now define double, triple &c functions very easily just like

this:

# let double = multiply 2;;

val double : int list -> int list = <fun>

# let triple = multiply 3;;

val triple : int list -> int list = <fun>

They really are functions, look:

# double [1; 2; 3];;

- : int list = [2; 4; 6]

# triple [1; 2; 3];;

- : int list = [3; 6; 9]

You can also use partial application directly (without the intermediate

f function) like this:

# let multiply n = List.map (( * ) n);;

val multiply : int -> int list -> int list = <fun>

# let double = multiply 2;;

val double : int list -> int list = <fun>

# let triple = multiply 3;;

val triple : int list -> int list = <fun>

# double [1; 2; 3];;

- : int list = [2; 4; 6]

# triple [1; 2; 3];;

- : int list = [3; 6; 9]

In the example above, (( * ) n) is the partial application of the ( * )

(times) function. Note the extra spaces needed so that OCaml doesn't

think (* starts a comment.

You can put infix operators into brackets to make functions. Here's an

identical definition of the plus function as before:

# let plus = ( + );;

val plus : int -> int -> int = <fun>

# plus 2 3;;

- : int = 5

Here's some more currying fun:

# List.map (plus 2) [1; 2; 3];;

- : int list = [3; 4; 5]

# let list_of_functions = List.map plus [1; 2; 3];;

val list_of_functions : (int -> int) list = [<fun>; <fun>; <fun>]

What is functional programming good for?

Functional programming, like any good programming technique, is a useful

tool in your armoury for solving some classes of problems. It's very

good for callbacks, which have multiple uses from GUIs through to

event-driven loops. It's great for expressing generic algorithms.

List.map is really a generic algorithm for applying functions over any

type of list. Similarly you can define generic functions over trees.

Certain types of numerical problems can be solved more quickly with

functional programming (for example, numerically calculating the

derivative of a mathematical function).

Pure and impure functional programming

A pure function is one without any side-effects. A side-effect

really means that the function keeps some sort of hidden state inside

it. strlen is a good example of a pure function in C. If you call

strlen with the same string, it always returns the same length. The

output of strlen (the length) only depends on the inputs (the string)

and nothing else. Many functions in C are, unfortunately, impure. For

example, malloc - if you call it with the same number, it certainly

won't return the same pointer to you. malloc, of course, relies on a

huge amount of hidden internal state (objects allocated on the heap, the

allocation method in use, grabbing pages from the operating system,

etc.).

ML-derived languages like OCaml are "mostly pure". They allow side-effects through things like references and arrays, but by and large most of the code you'll write will be pure functional because they encourage this thinking. Haskell, another functional language, is pure functional. OCaml is therefore more practical because writing impure functions is sometimes useful.

There are various theoretical advantages of having pure functions. One advantage is that if a function is pure, then if it is called several times with the same arguments, the compiler only needs to actually call the function once. A good example in C is:

for (i = 0; i < strlen (s); ++i)

{

// Do something which doesn't affect s.

}If naively compiled, this loop is O(n2) because strlen (s)

is called each time and strlen needs to iterate over the whole of s.

If the compiler is smart enough to work out that strlen is pure

functional and that s is not updated in the loop, then it can remove

the redundant extra calls to strlen and make the loop O(n). Do

compilers really do this? In the case of strlen yes, in other cases,

probably not.

Concentrating on writing small pure functions allows you to construct reusable code using a bottom-up approach, testing each small function as you go along. The current fashion is for carefully planning your programs using a top-down approach, but in the author's opinion this often results in projects failing.

Strictness vs laziness

C-derived and ML-derived languages are strict. Haskell and Miranda are non-strict, or lazy, languages. OCaml is strict by default but allows a lazy style of programming where it is needed.

In a strict language, arguments to functions are always evaluated first,

and the results are then passed to the function. For example in a strict

language, the call give_me_a_three (1/0) is always going to result in

a divide-by-zero error:

# let give_me_a_three _ = 3;;

val give_me_a_three : 'a -> int = <fun>

# give_me_a_three (1/0);;

Exception: Division_by_zero.

If you've programmed in any conventional language, this is just how things work, and you'd be surprised that things could work any other way.

In a lazy language, something stranger happens. Arguments to functions

are only evaluated if the function actually uses them. Remember that the

give_me_a_three function throws away its argument and always returns a

3? Well in a lazy language, the above call would not fail because

give_me_a_three never looks at its first argument, so the first

argument is never evaluated, so the division by zero doesn't happen.

Lazy languages also let you do really odd things like defining an infinitely long list. Provided you don't actually try to iterate over the whole list this works (say, instead, that you just try to fetch the first 10 elements).

OCaml is a strict language, but has a Lazy module that lets you write

lazy expressions. Here's an example. First we create a lazy expression

for 1/0:

# let lazy_expr = lazy (1/0);;

val lazy_expr : int lazy_t = <lazy>

Notice the type of this lazy expression is int lazy_t.

Because give_me_a_three takes 'a (any type) we can pass this lazy

expression into the function:

# give_me_a_three lazy_expr;;

- : int = 3

To evaluate a lazy expression, you must use the Lazy.force function:

# Lazy.force lazy_expr;;

Exception: Division_by_zero.

Boxed vs. unboxed types

One term which you'll hear a lot when discussing functional languages is "boxed". I was very confused when I first heard this term, but in fact the distinction between boxed and unboxed types is quite simple if you've used C, C++ or Java before (in Perl, everything is boxed).

The way to think of a boxed object is to think of an object which has

been allocated on the heap using malloc in C (or equivalently new in

C++), and/or is referred to through a pointer. Take a look at this

example C program:

#include <stdio.h>

void

printit (int *ptr)

{

printf ("the number is %d\n", *ptr);

}

void

main ()

{

int a = 3;

int *p = &a;

printit (p);

}The variable a is allocated on the stack, and is quite definitely

unboxed.

The function printit takes a boxed integer and prints it.

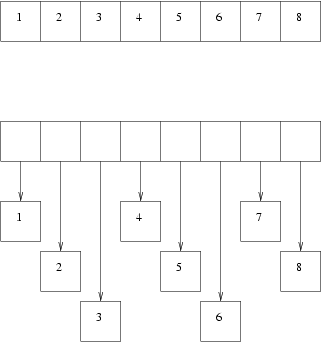

The diagram below shows an array of unboxed (top) vs. boxed (below) integers:

No prizes for guessing that the array of unboxed integers is much faster than the array of boxed integers. In addition, because there are fewer separate allocations, garbage collection is much faster and simpler on the array of unboxed objects.

In C or C++ you should have no problems constructing either of the two

types of arrays above. In Java, you have two types, int which is

unboxed and Integer which is boxed, and hence considerably less

efficient. In OCaml, the basic types are all unboxed.